Crosses: Harlem River

Connects: Washington Heights, Manhattan and Grand Concourse, Bronx, NY [satellite map]

Carries: 4 vehicular lanes, 2 sidewalks

Design: swing

Date opened: May 1, 1895

Postcard view: “Viaduct 155th Street, New York City.”

Macomb’s Dam bridge crosses the Harlem River, connecting West 155th Street in Manhattan with Jerome Avenue in the Bronx, just west of Yankee Stadium.

The Dam

The story of Macomb’s Dam Bridge dates back to 1813 when Robert Macomb, a local businessman, sought permission from the state legislature to build a dam across the Harlem River near 155th Street in Manhattan. He intended to turn the portion of the river between there and a dam he owned near King’s Bridge on Spuyten Duyvil Creek into a mill pond. The legislature granted permission for the dam on January 10, 1814, with a stipulation that a lock or some other mechanism for naval passage be built into the structure. In late 1813, when it became apparent that Macomb would be given permission to build his dam, a group of fifty prominent citizens petitioned the city’s Common Council seeking authorization for a bridge to be built on top of the dam. The petition mentioned Macomb’s approval for the idea, and an agreement to allow Macomb to charge tolls for passage over the bridge, with half of the toll money going to the city to help educate the poor. The Common Council announced the completion of the bridge on July 8, 1816, and recommended that the city build new roads in the area, which at the time was largely undeveloped, to take advantage of the new crossing.

When the dam was built, Macomb had a small lock, about 7 feet by 7 feet wide, installed on the Westchester County (encompassing what is now the Bronx) side of the structure. However, for unknown reasons, it was filled in with stone sometime in the late 1820s. For a while it was still possible for very small boats to pass through the openings between the piers supporting the bridge deck at high tide, but the trip was extremely hazardous. Several deaths were recorded when boats either overturned or broke apart during the passage.

Local citizens who had previously used the shores of the river for shipping coal, produce, and other materials began to organize an opposition to the obstruction caused by the dam. Robert Macomb had gone out of business by this point, and the ownership of the dam had passed through a number of hands. Complaints filed with the owners of the dam went nowhere, and the group enlisted the help of a young Lewis G. Morris.

The Nonpareil

Morris was of the belief that the obstruction of river navigation was illegal, so he devised a meticulous plan to reopen the river to traffic. He collected sworn statements from locals who had lived on the river before the construction of the dam, describing sloops and schooners sailing up the river to deliver cargo. Several times in early 1838, Morris took sail boats smaller than those described by the locals up the river to the dam, keeping detailed logs of the date, time, and the conditions of the water during the trip. Each time he reached the dam, he requested passage from the bridge tender. Each time, the bridge tender would turn him away, precisely as Morris expected, as such passage was impossible. On the night of September 14, 1838, Morris arranged for a shipment of coal to be delivered from Jersey City on board a boat named the Nonpareil to a dock he had built north of the dam in preparation for the plan. When the Nonpareil, with Morris aboard, reached the dam, passage through the dam was requested. Once again, the bridge tender refused to allow Morris through. When he did so, a band of about 100 men that had accompanied the Nonpareil on the last leg of her journey in an assortment of skiffs and flatboats went at the dam with shovels, axes, and other tools, tearing down a large enough section of the dam to allow Morris’ boat to pass through. When it was found that the tidal flow through the new opening was still difficult to navigate at anything but slack tide, the group returned the next week and spent three days tearing down additional sections of the dam.

William Renwick, the owner of the dam at the time, was furious, and attempted to have Morris arrested for disturbing the peace. When that failed, Renwick sued Morris for damages incurred to his property. In the Superior Court, Morris presented in his defense the original charter for the dam with its stipulation to allow navigation and the evidence he had collected showing that navigation, while once possible, was no longer so on account of the dam owner’s refusal. The court ruled that Morris had done nothing wrong. Renwick appealed the decision, and the Court of Errors affirmed the earlier decision. The case then went to the New York Supreme Court, where Justice J. Cowen ruled that the dam owners “have been guilty of a public nuisance” by obstructing the river with the dam. Having succeeded with his plan, Morris continued to act as an advocate for navigation and the improvement of the Harlem River, playing a major part in the construction of the High Bridge to carry the Croton Aqueduct over the river, the creation of the Harlem River Ship Canal, and other projects.

Central Bridge

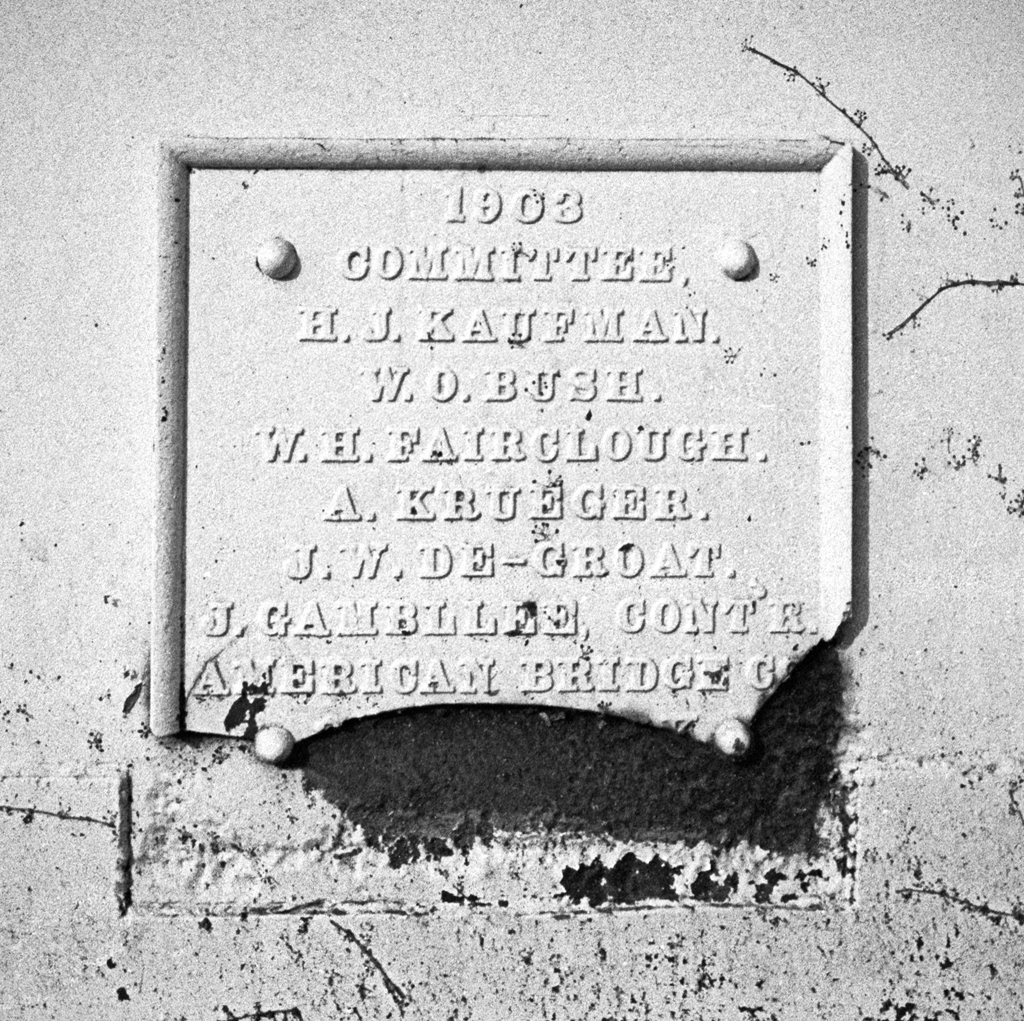

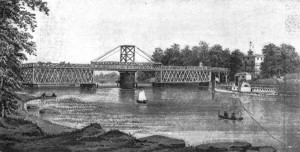

After the lengthy legal battle, the owners found themselves forced to maintain an opening in the dam. This arrangement worked for a while, but increasing traffic on the river caused many to call for the complete destruction of the dam, and to have it replaced with a proper movable bridge. On April 16, 1858, the City of New York and Westchester County were directed by the state legislature to remove the dam and build a free public bridge with a turntable opening, allowing navigation of the river at any time of the day. Lewis G. Morris and Charles Bathgate, a local landowner, were appointed as commissioners to direct the project. In 1861, Central Bridge, as it was named by the city, was completed.

Central Bridge was a wooden structure requiring frequent repairs. Large portions of the bridge had to be rebuilt entirely. The square swing frame was replaced by a wooden “A” frame in 1877. The wooden approach spans were replaced by iron spans in 1883. These repairs did not seem to help much, as an 1885 New York Times article showed. “They ought to keep it for clam wagons,” said Lawson N. Fuller, a local horse racer, “though no clam with any regard for himself would ever cross the bridge if he could help it” (A Patchwork of Wood). In October 1887, the city’s Board of Estimate and Apportionment, which controlled the city’s finances, balked at the estimated $60,000 needed to once again bring the bridge into a usable state of repair, and suggested that money would be better spent on a new bridge or a tunnel under the river. The tunnel idea was very popular with local residents who were tired of travel delays incurred by frequent bridge openings. The city elected to build a new bridge, however, and an Act of Legislature passed in 1890 authorized its construction.

Macomb’s Dam Bridge

Alfred P. Boller was chosen as the head engineer of the construction of the new bridge. Boller had a solid reputation as a structural engineer with an eye for aesthetics, which was apparent in the design he selected for the new bridge.

Macomb’s Dam Bridge is a swing bridge, with a span that rotates on a center pivot to make way for boat traffic on the river. The movable span is a 415-foot long Pratt through truss structure with a rectangular central tower adorned with decorative finials and top chords gracefully curving down to the deck with a concave profile. At the time of construction, the span was said to be the heaviest movable structure in the world. The piers that support the ends of the movable span when in the closed position are constructed of granite, with large archway openings on the bottom. On top of both ends of the piers are stone gate tender’s houses with red shingled pyramidal roofs.

The approach on the Manhattan side is composed of a V-shaped intersection, with Macombs Place, formerly Macomb’s Dam Road, on the south, and West 155th Street, carried on a large viaduct on the west. The 155th Street Viaduct was built at the same time as the bridge, and was also designed by Boller. It is 1600 feet long and about 61 feet feet wide. It is a steel structure, composed of deck girder spans carried on two parallel rows of steel columns across the valley from the heights above Harlem.

The approach on the Bronx side of the bridge is composed of two Warren deck truss spans on masonry piers, six steel girder spans installed between 1949 and 1951 with the construction of the Major Deegan Expressway, and most noticeably, a 221 foot camelback through truss carrying the roadway over the Metro-North tracks below.

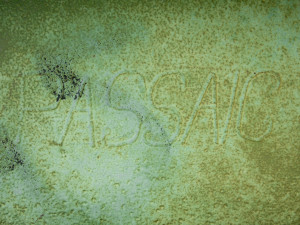

Construction of the bridge began in 1892, and the old bridge was moved up the river to a set of temporary piers at 156th Street to act as an alternative crossing while the new bridge was being built. The swing span and Bronx approaches for the bridge were built by the Passaic Rolling Mill Company of Paterson, NJ. The 155th Street Viaduct was built by the Union Bridge Company of Athens, PA. The ornamental iron railings and stairways on the bridge and viaduct were made by Hecla Iron Works of Brooklyn.

The bridge opened to traffic on May 1, 1895. An announcement published in the next day’s New York Times said simply, “The new Macomb’s Dam Bridge, which crosses the Harlem River at One Hundred and Fifty-fifth Street, was opened at 9 o’clock yesterday morning. There was no particular ceremony” (New Macomb’s Dam Bridge Opened).

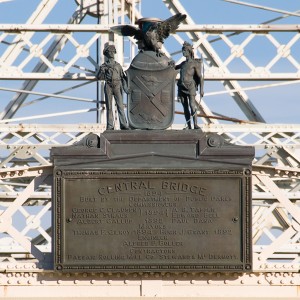

The official name for the new bridge was also Central Bridge, as indicated by the ornamental plaque that still exists on the western side of the swing span. That name, however, never fell into popular use, with almost all New Yorkers continuing to refer to it by its old name, Macomb’s Dam Bridge. Martin Gay, Bridge Commissioner for the city in the early 1900’s decried the Central Bridge name as being “meaningless” (1904, Harlem River Bridges). A resolution by the Board of Alderman officially renamed it as Macomb’s Dam Bridge on November 11, 1902.