Location: Branch Brook Park, Newark, NJ [satellite map]

Carries: 2 vehicular lanes, 2 pedestrian sidewalks

Design: Arch bridge

Date opened: 1900

Postcard view: “Branch Brook Park West Arch Bridge”

Essex County, New Jersey is home to twenty Olmsted parks–those designed by firms headed by members of the prominent Olmsted family: Frederick Law Olmsted Senior or his nephew/stepson John Charles Olmsted and son Frederick Law Olmsted Junior [1]. The largest of New Jersey’s Olmsted parks is Branch Brook Park in Newark.

In 1867, after the New Jersey State legislature authorized the creation of a Newark Park Commission, Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. of Central Park fame recommended a site in Newark which would eventually become Branch Brook Park. Sixty acres of land were set aside for park use; Olmsted along with his partner Calvert Vaux planned for the park to be a “central park” for the City of Newark. In 1895 the Essex County Parks Commission was created, making Branch Brook Park the first public county park opened in the United States. Initially John Bogart and Nathan Barrett designed the park, and work on it began in 1896. However, the Parks Commission became dissatisfied with the romantic garden-inspired design and instead hired the Olmsted Brothers firm of John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. in 1898 to finish the park with a more naturalistic look. It was sixty acres large at its start, but over time has grown to nearly 360 acres; much of area was donated by prominent local families.

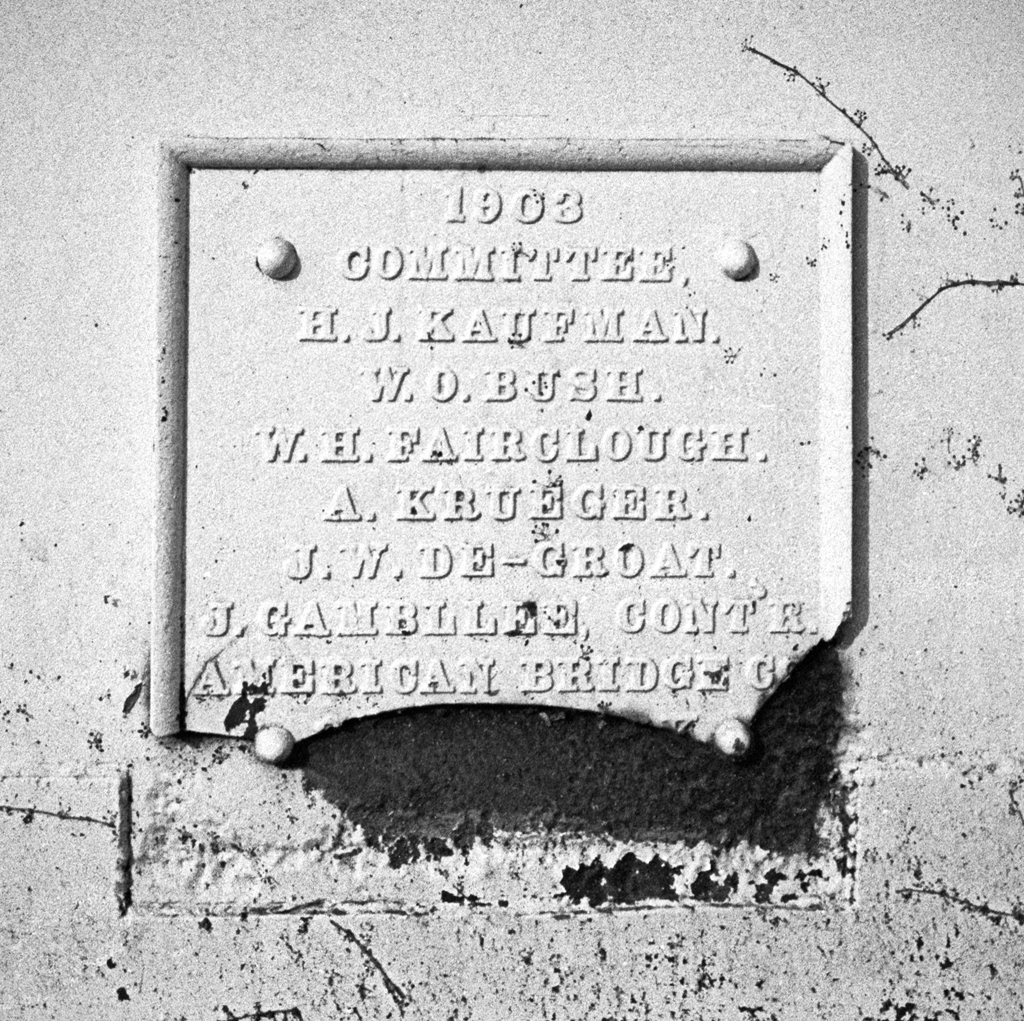

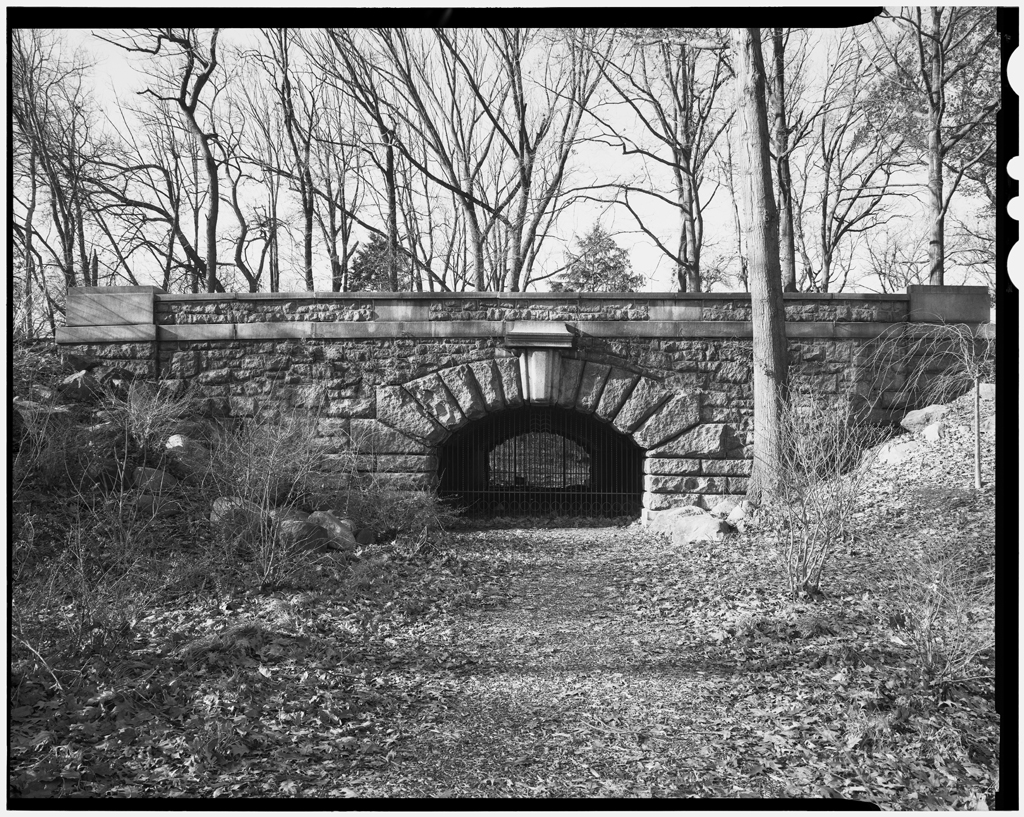

The park is home to many architecturally significant structures, including bridges, buildings, gates, and sculptures. Many of these were designed by the beaux-arts architectural firm of Carrère and Hastings headed by John Merven Carrère and Thomas Hastings. The pair designed two Subway Bridges now referred to as Subway 1, East and Subway 2, West. They were included in the initial Barrett and Bogart plan for the park but were redesigned and moved when the Olmsted Brothers took over; they were originally called the East Arch and West Arch. Both bridges have undergone rehabilitation work to remove graffiti, repair masonry, and remove vegetation where it is harmful to the structure.

Subway 1, East

The East Arch was designed by Carrere & Hastings 1898 and constructed between 1989 and 1900. It is located on the eastern side of the Branch Brook Lake and was designed to help pedestrians avoid traffic on the park’s main thoroughfares, at the time used mainly by horses and carriages. An unpaved path passes under the granite bridge (hence the later naming of “subway”). The bridge is a stone arch design with a rustic granite masonry facing. Its railings are large granite blocks and its barrel-vaulted interior is lined with yellow bricks.

Subway 2, West

The West Arch is similar in design to the East Arch and was designed and built at the same time. The West Arch underpass was was at some point referred to as “Lovers’ Lane,” as seen in a ca.1911 postcard. However, it suffered more over the years than its counterpart in the east from neglect and vandalism–much more vegetation had infiltrated the structure and mineral deposits had formed within the arch to the point that stalactites hung from the ceiling; portions of the brick had fallen out entirely. The underpass is currently sealed off, so it is only possible to walk over, not under, Subway 2.