Crosses: Harlem River

Connects: Manhattan and the Bronx [satellite map]

Carries: Pedestrian/bike path; formerly carried the Old Croton Aqueduct in its interior

Design: Stone arch bridge with steel arch section

Date opened: 1848

Postcard views: bridgesnyc.com/postcards

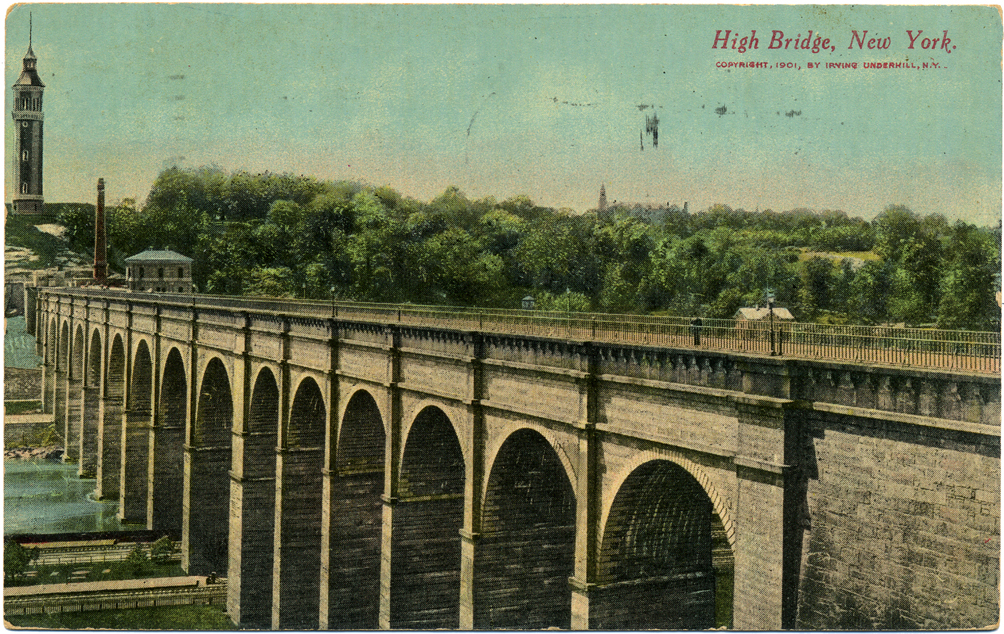

The High Bridge, also known as the Aqueduct Bridge, opened in 1848 and is the oldest extant bridge in New York City. The bridge was built to carry the Croton Aqueduct into New York City from upstate New York. It crosses the Harlem River, connecting High Bridge Park in Manhattan with the Bronx near West 170th Street.

Need for Water

Providing a supply of drinking water has long been a problem for the island of Manhattan. Surrounded by brackish water (an undrinkable mixture of salt and fresh water), in its early days, the city got its water from wells, cisterns, and natural springs. However, the city was constantly growing and expanding northward; it grew especially quickly in the years following the Revolutionary War. The limited sources of fresh water available became polluted and diseases such as yellow fever were rampant. The city’s first cholera epidemic began in 1832 and infant mortality soared. The wealthy paid to have their water delivered, but the poor, living in overcrowded, unsanitary conditions, had no options other than to drink polluted water. In 1832, Colonel DeWitt Clinton, of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, proposed building an aqueduct to supply the city with water from the Croton River, north of the city in Westchester County.

High or Low

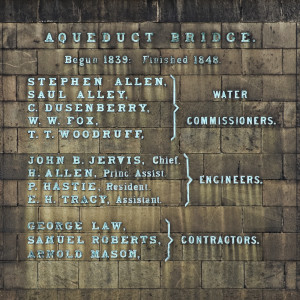

A temporary water commission was created in 1833 with civil engineer David Bates Douglass appointed as chief engineer to plan for a new water supply. Douglass proposed a high stone arch bridge across the Harlem River as part of his plan to carry water 40 miles from Westchester to the Croton Distributing Reservoir, built between 40th and 42nd Street in Manhattan (a site currently occupied by Bryant Park and New York Public Library’s main branch, the Stephen A. Schwarzman building). The Water Commission was formally established in 1834, and more surveys were done, including one by John Martineau, which included a low bridge which would cost less but block more of the river. Martineau’s plan was initially approved in 1835. On December 16 of that same year, the Great Fire of New York began in a Merchant Street warehouse; the city was ill-equipped to fight it and the need for a sufficient water supply was yet again in the headlines. The Board of Water Commissioners, favoring a low bridge, quietly replaced Douglass with John Bloomfield Jervis in 1836; Jervis was well-known as chief engineer of the Erie Canal. Jervis surveyed and planned for the low bridge, but opposition came from the Board of Aldermen in 1838, with the argument that the low bridge would impede navigation on the Harlem River. At the time, the river was already obstructed–Macomb’s Dam to the south and mills in the Kingsbridge section of the Bronx were both impassible. Though a decision had yet to be reached, the Water Commission began to build a low bridge across the Harlem River in July, 1838. That work was halted in May, 1939 when the State Legislature stepped in, giving two choices: a high bridge (allowing at least 100 feet of clearance under the bridge) or a tunnel under the river. Jervis drew up plans and construction began in August, 1839.

High Bridge Design

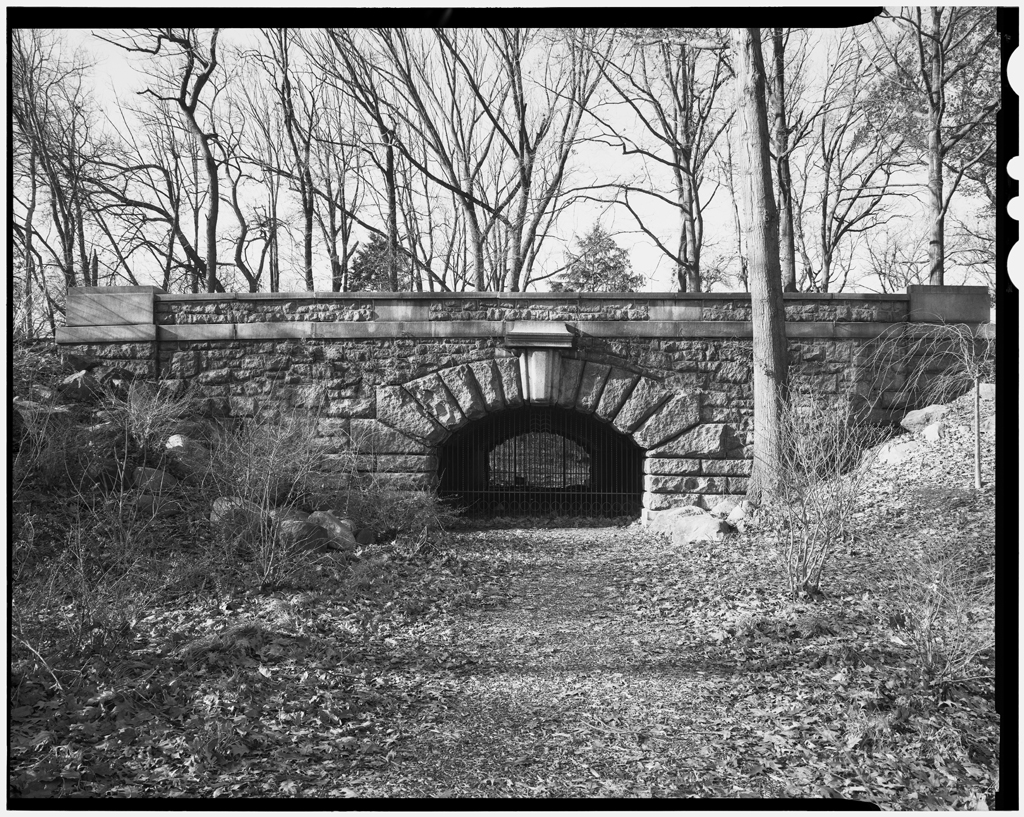

The bridge built consisted of 15 circular stone arches and had a clear height of 114 feet at high tide. It was meant to look like Roman aqueducts, though many modern innovations were employed. One was making the piers hollow to lessen dead weight, at the same time allowing water to drain back to the river. An opening gala for the Croton Aqueduct was held on July 4, 1842, and a celebratory parade followed on October 14. All this celebration was somewhat premature in terms of the High Bridge, as it wasn’t fully completed until 1848; temporary pipes carried the water until it was finished. The city continued to grow, as did its water needs. By 1850, the two original 36-inch pipes in the bridge were seen as inadequate, but it took until 1861 to install a third, 90-inch pipe. Between 1866 and 1872, the 200-foot-tall High Bridge Water Tower (also designed by John B. Jervis) and a seven acre reservoir were built to allow water to flow to residents in Manhattan’s higher elevations. It, along with a reservoir Soon, the Croton Aqueduct itself was unable to keep up with the city, and more aqueduct projects were envisioned. The New Croton Aqueduct opened in 1890, followed by the Catskill Aqueduct system, partially opened in 1916 and fully completed by 1924.

Threat of Destruction

World War I brought changes and threats to the High Bridge’s continued existence. On February 3, 1917, the High Bridge Aqueduct was closed. It was feared that wartime saboteurs could destroy the aqueducts and flood the city [1]; since the city already had two newer aqueducts to guard, the Old Croton was shut down so it wouldn’t have to be patrolled. It was eventually put back into service, but was never again seen as necessary. The Harlem River was used extensively for shipping during World War I and the High Bridge’s piers came to be viewed as a hazard–obstructions that had existed during the bridge’s construction, such as Macomb’s Dam, had been dealt with long ago (the dam had been replaced by a swing bridge in 1861). The Army Corps of Engineers ordered the removal of the piers that were in the river, and that turned into a suggestion by the city to simply demolish the bridge altogether. New York City’s citizens as well as numerous professional engineering organizations protested, and debates followed for the next several years. In March of 1923 it was decided that the bridge would be spared so long as a larger channel could be opened for navigation [2]. Plans for a cantilevered arch design were approved by the Municipal Arts Commission in July 1925. A New York Times article stated that, “from a distance, the projected single span will harmonize with the Washington Bridge” [3]. Five of the original arches were replaced with one steel span in 1927 [4]. The replacement steel arch has never evoked the same feelings as the stone arches, as Christopher Gray described in a 2013 New York Times article:

To see the bridge from a distance, the engineering pilgrim can brush by the piers at speed on the north- and southbound Major Deegan Expressway. But a more contemplative view can be had from Depot Place, a tiny stub off Sedgwick Avenue just south of the bridge. There, the granite piers start out from the Bronx shore in perfect majesty, only to be brought to an unseemly halt at the river. [5]

Closing of the Old Croton Aqueduct

Once both the New Croton Aqueduct and Catskill Aqueduct had been opened, the original Croton Aqueduct essentially became obsolete. The Croton Distributing Reservoir was torn down in the 1890s, but the “Old” Croton Aqueduct was still used to fill the Croton Receiving Reservoir, located in Central Park, until 1940, when Commissioner of Parks and Recreation Robert Moses had it taken out of service. The reservoir was filled and is now Central Park’s Great Lawn.

Closing of High Bridge

High Bridge remained open as a pedestrian path, though water had long ceased to flow within it. Rumors abound as to the exact reason for the eventual closure of the path, but a common one is that someone taking a Circle Line cruise up the Harlem River was either hurt or killed by rocks flung from the bridge. A New York Times article from April 21, 1958 states that:

Four passengers on a sightseeing boat were hurt yesterday when a gang of juveniles hurled sticks, stones and large pieces of brick from a bridge as the ship passed below. The bombardment started just as the Circle Line’s excursion boat No. 8 steamed into the shadow of High Bridge on the Harlem River. [6]

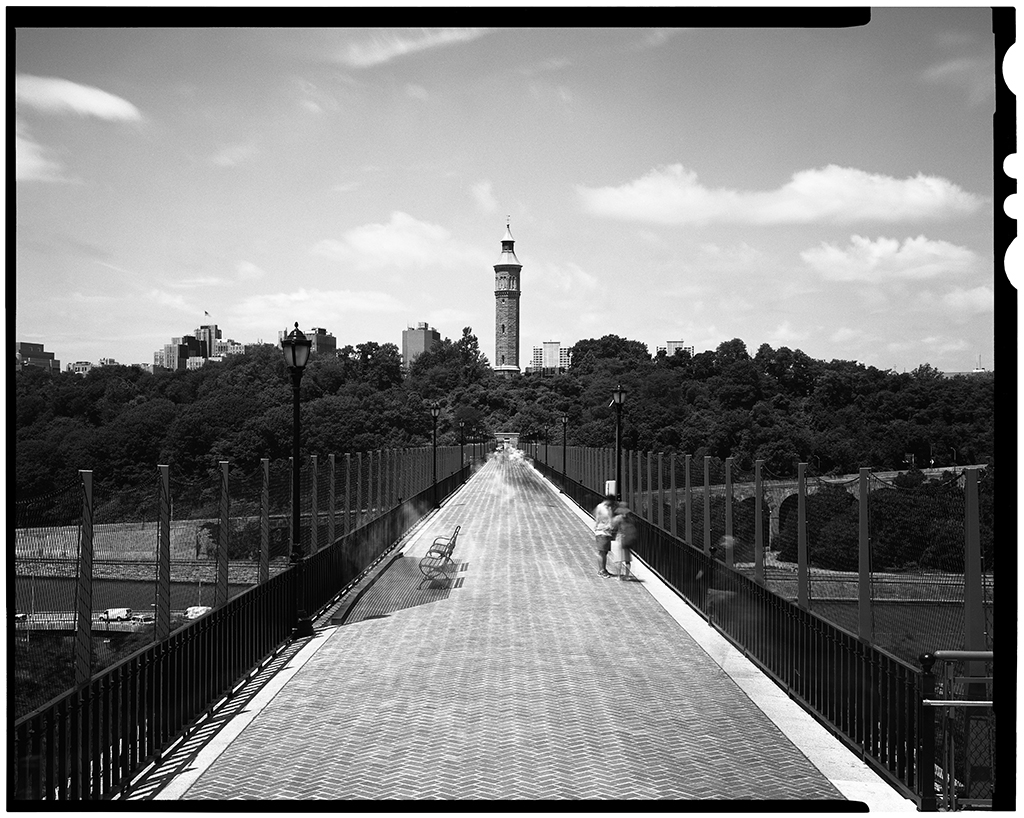

Being hit from above on the Harlem River was nothing new; in 1904 a group of oarsmen asked for police protection from “stone-throwing hoodlums who infest the various bridges over the Harlem River” [7]. Regardless of the reason, the pedestrian path was closed in the 1970s. The High Bridge was designated a New York City Landmark by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1970 [8]. It was also made a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1975, and a National Historic Landmark in 1992. Designations aside, the bridge had fallen into a state of disrepair; Sharon Reier lamented in 1977 that “the lofty structure is now fenced off with tangles of barbed wire reminiscent of the Berlin Wall.” [9]

Reopening

The bridge sat unused for many years, other than by those brave enough to scale its barbed wire fence. Pedestrians crossed the Harlem River on the Washington Bridge several blocks to the north, a busy bridge with a narrow pedestrian lane. In 1995, 10-year-old homeschooled Maaret Klaber attended a community board meeting and asked the park committee to reopen the walkway [10]. It would be a long wait, but in 2006 the Department of Parks and Recreation announced plans to reopen the bridge, though many hurdles still remained before work could begin. Advocacy groups, including the Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct and the High Bridge Coalition, pushed for its reopening and work began in 2012, based on a 2011 New York City Parks Department plan [11]. The restoration, financed by the city and supplemented by Federal Highway Administration funds, cost over $60 million. The bridge’s stone joints were re-mortared, its brick walkway was cleared of plants and repaired, its cast-iron fencing restored (and 8-foot-high safety netting was added outside of the decorative fencing), new lighting and ramps were added, and its steel arch was repainted. After more than 40 years, the bridge reopened to the public on June 4, 2015.