Crosses: Flushing River

Connects: Corona and Flushing, Queens, NY [satellite map]

Carries: 4 vehicular lanes, 2 sidewalks, IRT 7 subway

Design: double-leaf bascule

Date opened: May 14, 1927

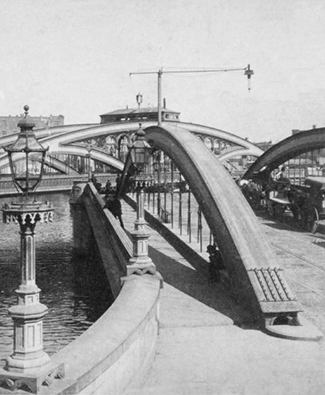

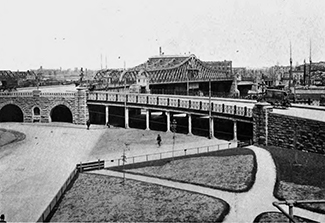

The Roosevelt Avenue Bridge is a double-deck, double-leaf bascule movable bridge over the Flushing River in northeastern Queens. It carries four lanes of Roosevelt Avenue and two sidewalks on its lower deck, and three tracks of the IRT Flushing / 7 train line of the New York City Subway on its top.

Planning

Surveying for the bridge began in 1913 as part of an extension of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company’s Woodside and Corona line. The original plan had the line mapped out between 42nd Street in Manhattan and Prime Street in Corona, with the extension reaching out to the village of Flushing, with a possible further extension to Little Neck at the city line. The line reached Corona in 1917, but United States involvement in World War I prevented further construction. Financial problems after the war delayed progress still until 1921, when city engineers began negotiations with the US War Department concerning what type of structure the city could build to cross the Flushing River. The War Department, which had jurisdiction over all navigable waterways and their crossings in the country at that time, denied a request by the city to be allowed to build a simple fixed bridge across the river on account of it being an obstruction to river traffic. A tunnel was briefly considered, but was decided against when cost estimates for it reached $2,500,000, more than the city was willing to pay. The War Department suggested the city build a bascule bridge, and officials relented.

Construction

Groundbreaking for the bridge was held on April 21, 1923 in a ceremony attended by Mayor John Hylan and Maurice E. Connolly, Borough President of Queens. Construction began soon after, though many delays occurred due to a recurring problem with the foundations of the bridge settling in the deep mud on the banks of the river. On May 14, 1927, the bridge was opened to pedestrians and a bus line was established between downtown Flushing and Willet’s Point Boulevard station, the temporary terminal of the line while the foundation issues were being resolved. Train service would not begin across the bridge until January 21, 1928, with a special train for city officials making the inaugural run from Time Square to the new station in Flushing. The extension to Little Neck has yet to be built.

The final cost of the bridge was $2,640,000, more than the estimated cost of a tunnel under the river, even when adjusted for inflation. Despite the additional cost the city was required to pay for a movable bridge, the need to keep the river open to navigation did not last long. When construction of Flushing Meadows Park was under way in 1939, park engineers realized a dam was needed to keep the tides of the East River from inundating the low-lying fields. The Long Island Railroad, which runs just a few hundred feet upriver from Roosevelt Avenue, agreed to replace the swing bridge they owned over the river with a combined embankment and tidal gate on top of which they would continue to operate their trains. With no docking facilities in place between the two structures, navigation of the Flushing River effectively ended at the Roosevelt Avenue bridge. In 1961, construction of the northern extension of the Van Wyck Expressway began, and the route of the highway was driven directly through the navigation channel of the bridge, supported over the river by concrete piers. The operating mechanisms and bridge tender’s controls were finally removed at that point, and the bridge has not opened since.

Design

The Roosevelt Avenue bridge was the largest trunnion bascule bridge in the world when it was completed. It was designed by Edward A. Byrne and Robert E. Hawley of the NYC Department of Plants and Structures, and built by the Arthur McMullen Company of New York. The channel of the river at the point of the bridge is only 70 feet wide, but because of the skew of the route over the river, the clearance between the bridge piers is 162 feet. Together, the lift leaves are 153 feet long, and each weighs approximately 4 million pounds, supported by a truss structure 25 feet 6 inches deep. The piers that support the leaves are of poured concrete construction, with granite blocks covering the facings exposed to the water. Each pier measures 92 feet by 118 feet, and contains a large hollow space inside to accommodate the movement of the bridge’s counterweights.

Future

In January, 2010, the NYC Department of Transportation announced plans to rehabilitate the bridge starting in 2012. Years of neglect have resulted in a need to replace the road deck, repaint and repair rust on the steel truss and approach structures, and repair deteriorating concrete. The city also plans widen the sidewalks from 8 to 10 feet and establish bike lanes within them. The project is expected to be finished in 2015.

Update (04/29/2015): Rehabilitation has been delayed and is now expected to begin in mid-2015 with an end date to be determined.