Crosses: Hackensack River

Connects: Hackensack and Bogota, NJ [satellite map]

Carries: 2 vehicular lanes, 1 sidewalk

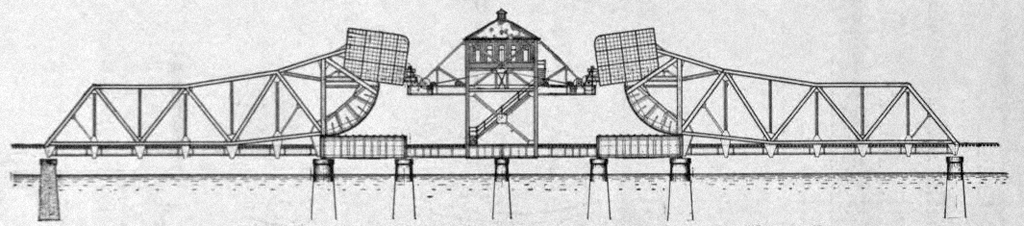

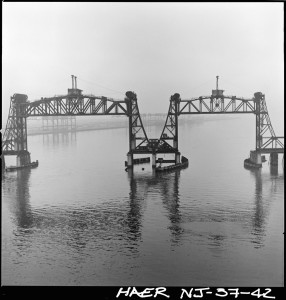

Design: (former) swing bridge, fixed into place in 1984

Date opened: 1900

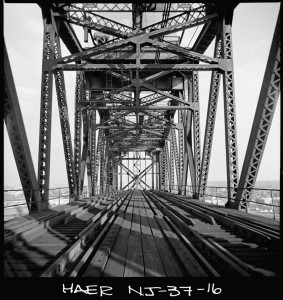

The Midtown Bridge, also known as the Salem Street Bridge and William C. Ryan Memorial Bridge, is a fixed through truss bridge that was formerly a swing bridge. It spans the Hackensack River, connecting Hackensack and Bogota in Bergen County, New Jersey.

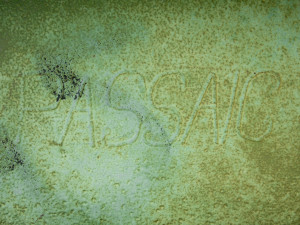

The bridge was originally built in 1900 by F.R. Long and Company as a trolley bridge for the Bergen County Traction Company. Steel for the bridge was provided by the Passaic Rolling Mill Company of Paterson, NJ. The bridge’s original design was a through Pratt truss swing span on a stone center pier and it carried two sets of tracks. The Bergen County Traction Company had been formed in 1894, and opened in 1896, connecting ferry passengers traveling from Manhattan to Edgewater to trolley lines to Fort Lee, Leonia, Englewood, Teaneck, Bogota, and Hackensack. The lines were consolidated in 1900 into the New Jersey and Hudson River Railway Company and later sold to the Public Service Corporation of New Jersey in 1910. The Bergen Division of the Public Service Railway continued to carry trolleys over the Hackensack (a 1937 image can be seen in Figure 139 (page 189) of Streetcars of New Jersey: Metropolitan Northeast [1]).

However, with the rise of the automobile, transportation was changing, and trolley routes began to be replaced by buses. By 1938 all trolleys had been discontinued in Bergen County; the bridge’s tracks were replaced with a steel deck and in 1940 the Midtown Bridge began carrying vehicular traffic. It continued to operate as a swing bridge until a rehabilitation project in 1984, when it was fixed in place and its machinery was removed. In 1980, the bridge was given the additional name of “Ryan Memorial Bridge,” named after Bogota resident and U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant William C. Ryan, who was killed in North Vietnam in 1969.

The Midtown Bridge has only recently been notable for being in need of repair. It was shut down for several weeks in 1998 by the Department of Public Works so that emergency repairs could be made to its steel joints. The issue was described by county engineer Robert Mulder as “an ongoing problem that needs to be permanently fixed” [2]; however, that fix has been continually delayed. A project to rehabilitate the Court Street Bridge, another former swing bridge in Hackensack downriver from the Midtown Bridge, meant that it was closed from 2010-2012, with much of the Court Street Bridge’s traffic diverted to the Midtown Bridge during that time. On October 17, 2013 the Midtown Bridge was shut down for emergency repairs again; Bogota’s Council President and Office of Emergency Management coordinator Tito Jackson had noticed a large separation in the bridge’s metal decking at its joints [3]. The current plan is to replace the aging span with a bridge with a concrete deck. Bergen County is home to a number of bridges in need of major repair or replacement, so there is no timetable for the project as of yet.